Standing Rock struggle being waged with posts and prayers

The 2016 election emphasized how the world has entered an era where all issues are inevitably twisted beyond recognition through the use of propaganda and some outright lies in social media but also traditional sources. Each side digs in, believing or at least supporting their cause and talking points, even if untrue.

The most recent example is the battle over the Dakota Access Pipeline, playing out on the Internet as much as it is on the ground. Both sides skew their messages, appealing to their supporters. But so far, it’s the law officers, backed by the pipeline company Energy Transfer Partnership and governor of North Dakota, who have slid farther into falsehood.

The evolution of the Standing Rock struggle demonstrates the dangers of allowing industry, particularly oil and gas, to police itself. It also raises questions about the corrupting influence of money in politics at the state and federal level and the damage it causes to a democracy once intended to be of the people, for the people and by the people.

--

In December 2014, Dakota Access LLC, part of Houston-based Energy Transfer Partners, submitted to the North Dakota Public Service Commission its final application to build a crude oil pipeline from the Bakken oil fields to refineries in Illinois. The route passes about a mile north of the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation.

Dakota Access claims that during scoping, it "immediately" rejected an alternative that would have installed the pipeline 10 miles north of Bismarck, North Dakota's capital. North Dakota PSC Chairwoman Julie Fedorchak told said the Public Service Commission didn’t evaluate the Bismarck option because Dakota Access had already taken it off the table, according to the Forum News Service, a Midwestern newswire service.

By November 2015, Dakota Access had written its own environmental assessment that it submitted to the Army Corps of Engineers. Normally, federal agencies write their own environmental assessments or impact statements for a project, but not in this case.

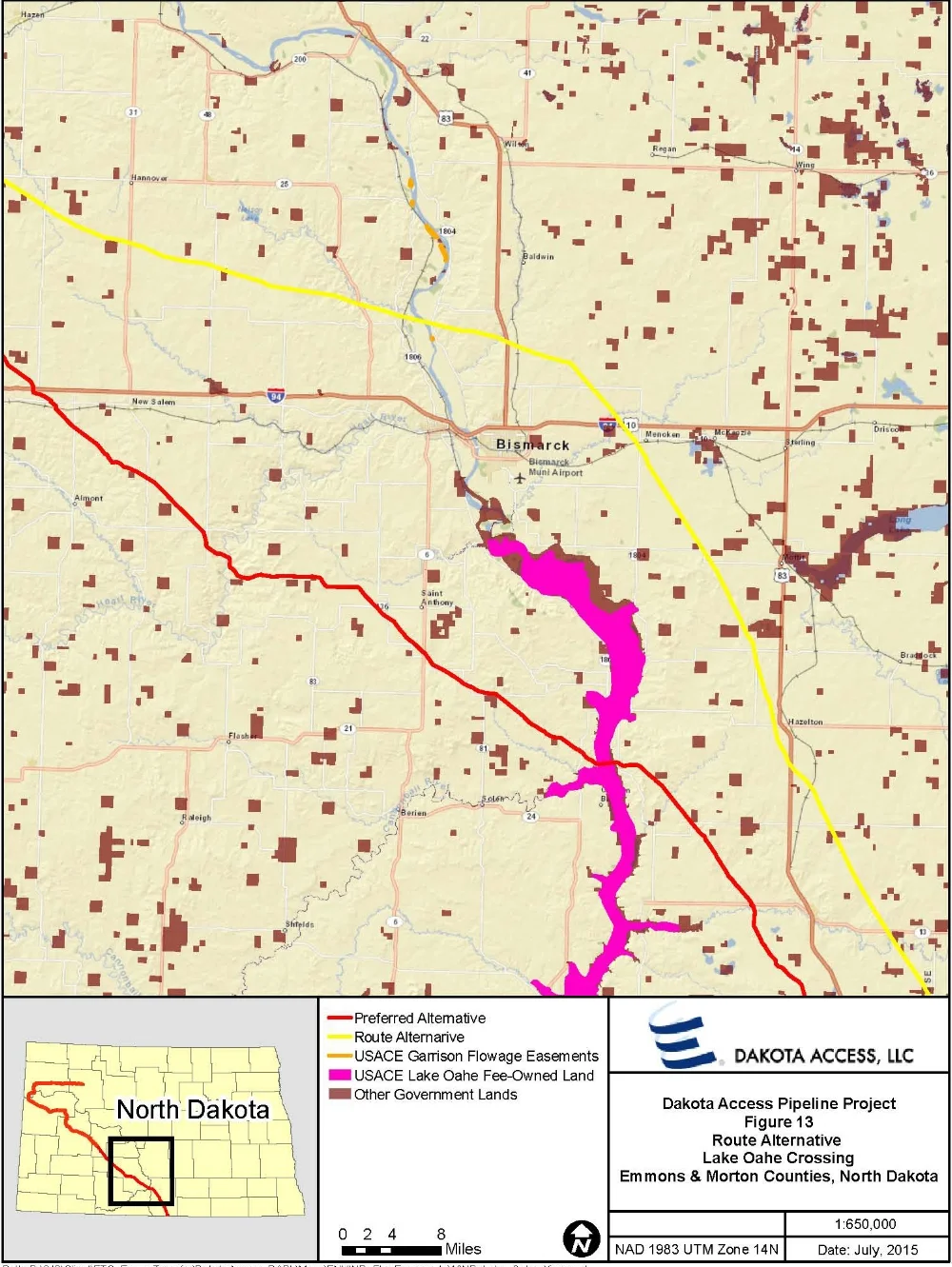

After claiming that sufficient quantities o crude oil could not be shipped by means other than a pipeline, Dakota Access explained why it rejected the Bismarck route: "wellhead sourcewater protection areas were prevalent due to the proximity of the city" and "the route alternative included approximately nine additional miles of pipeline to cross north of Bismarck," which would increase the cost of the project. It also said the Bismarck route would have crossed on or near a great number of state and federal lands, even though the current route cuts through a large swath of the USACE fee-owned property at Lake Oahe. But the assessment doesn't provide any analysis to prove these assertions.

Most pertinent to the current conflict: the route map designed by Dakota Access (see figure below) doesn't depict the Standing Rock Reservation, which is a huge federal area extending south of State Highway 24 to just south of where the pipeline is to cross Missouri River. Except for including the Standing Rock Office of the Bureau of Indian Affairs as a contact, there is no mention in the report of Standing Rock.

People in the northeastern portion of Standing Rock depend on the Missouri River for their domestic water supply. So tribal elders question why the route was altered to protect Bismarck's water wells only to potentially threaten their own water supply? As those in Billings and Glendive, Mont., know, pipeline breaks in rivers can degrade drinking water for months.

Of the three dozen entities - including three Bureau of Indian Affairs offices - that Dakota Access claimed to consult for the November 2015 draft report, only six commented during the USACE comment period in April 2016. According to the list in the report, no tribal governments were contacted and none commented. As a result, on July 25, USACE Colonel John Henderson concluded that granting permits to drill beneath Lake Oahe didn't "constitute a major federal action that would significantly affect the quality of the human environment. As a result, I have determined that preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement is not required."

The Standing Rock tribes immediately sued for an injunction against the USACE permits because the USACE had not properly consulted with the tribe as a sovereign nation as required by law. Pipeline proponents argue that the Standing Rock Sioux have no right to complain since they didn't comment when they were supposed to. But the Sioux said Dakota Access knew of their opposition from the start, said Dave Archambault II, chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe.

"Our concerns were clearly articulated directly to them in a tribal council meeting held on Sept. 30, 2014, where DAPL and the ND Public Service Commission came to us with this route. We have released the audio recording from that meeting," Archambault said in a Nov. 25 statement.

As Dakota Access began building the pipeline, the Sioux established their spiritual camp by the Cannonball River. Since then, more tribes and other supporters have flocked to Standing Rock, and clashes with law enforcement continue. As more Americans have become aware, each side has turned to the Internet to lobby for their actions.

In early September, a contentious series of events boosted indignation on both sides. A judge denied a Standing Rock's injunction. But shortly after, the departments of the Army, Justice and Interior departments ordered Dakota Access to stop building the pipeline within 20 miles of the Missouri River while the government reconsidered.

Energy Transfer Partners CEO Kelsey Warren wrote a memo to his employees, saying that the pipeline was 60 percent complete so "we intend to meet with officials in Washington to understand their position and reiterate our commitment to bring the Dakota Access Pipeline into operation."

Standing Rock inhabitants were angered when Dakota Access then ignored the voluntary order and continued construction. A few chained themselves to bulldozers. Then the company plowed through an area that Standing Rock elders had identified in court documents as sacred or historic. When the Sioux tried to defend the area, private security guards hired by Dakota Access used mace and attack dogs against them. Protesters had started live-streaming to document police actions, and the tribes started to use video drones to film the pipeline's progress.

The state and Morton County took over law enforcement, and N.D. Gov. Jack Dalrymple requested help from other states through an emergency management assistance compact. But as witnesses challenged police claims of violence as police faced unarmed protesters over a pipeline that would benefit an oil company, several states pulled their officers back, including Wisconsin and Montana. The state of North Dakota isn't the protesters' target, but many of North Dakota's elected officials back the pipeline. That's because oil drives North Dakota's economy to the tune of more than $5 billion in oil-related tax payments. So it's not surprising that most in North Dakota, from the governor down to the Bakken bartenders, side with Dakota Access.

Most recently, the Army Corps announced on Nov. 25 that the protesters would be forced off USACE land where the camp now sits, and then the corps reversed itself three days later. In response, Dalrymple announced on Nov. 29 that he would evict the protesters, citing safety concerns that the Blackwater Bridge roadblock built by law enforcement wouldn't allow emergency vehicles through. In both cases, the public flooded both the USACE and the governor's offices with calls and emails after each decision. After Kirchmeier recently threatened to give supporters carrying supplies a $1,000 fine, Dalrymple clarified on Nov. 30 that no supporters would be forced out or stopped on their way to Standing Rock.

--

Those are the documented facts that set the stage for the social media tug-of-war that is most evident when deputies clash with protesters.

Reporters often talk only to law enforcement representatives, so their stories can be one-sided with the Morton County Sheriff's Department front-and-center. Morton County Sheriff Kyle Kirchmeier has regularly claimed that protestors are violent and called each encounter a "riot," so he can justify the use of water cannons, flash grenades, tear gas and rubber bullets. His police wear riot gear and employ two to three military-surplus assault vehicles, one of which has an LRAD noise cannon. Kirchmeier says he's just doing his duty.

Hundreds of protesters have been forcibly arrested - few have resisted arrest - only to have charges either dropped or thrown out of court. That's not to say that some protesters don't break the law or invite police violence.

Protest organizers - some of whom are now aligned with Black Lives Matter, the American Indian Movement, The Indian Problem and PICA - coach those who would participate in daily actions to be peaceful and prayerful; to stay together and follow instructions. They coordinate with the tribe to select and conduct actions that are peaceful - violent demonstration is not condoned by tribal elders. Plus, they wouldn't receive as much worldwide support if they were violent, and violence would give law enforcement agencies justification to hit back, as the sheriff's comments demonstrates.

But an hour of instruction doesn't sink in for some protesters; some don't attend the training; and there are always those who get panicked, emotional or carried away. Many are college kids who have faced little opposition in their cloistered lives, and their stress level skyrockets when they see grim-looking police pull up carrying rifles and mace cylinders. They start yelling and the lines break as courage fails for some. Prayerful people shouldn't taunt police, but videos are full of people talking back. But none of these incidents look like Ferguson with violence and looting. There's sass but no mass hysteria.

Still, people in the nearby farms and communities of Mandan and Bismarck are critical of protests and the people holding them in their community.

Organizers know people will be arrested for misdemeanors like trespassing when they enter a mall, and sometimes that's the point. They are engaging in civil disobedience, not violent crime, and most are willing to be arrested to raise awareness. So organizers try to prepare protesters to cooperate during a normal arrest. Unfortunately, some protesters have come back with stories of arrests that aren't normal. They say police are using humiliating tactics, including strip searches, physical roughness and isolation.

One person asked why protesters wear bandanas over their faces if they aren't breaking the law. In most cases, it's a pathetic defense against tear gas, along with goggles from high school chemistry class. Organizers ask protesters to show their faces because they are supposed to be prayerful. That's also why they ask the police officers - many of whom have their badges taped over to cover their names - to raise their visors or take off their helmets. To their credit, a few officers do.

Many Americans automatically trust law enforcement officers, having been taught that they are there to serve and protect. But history and headlines are replete with stories about police and particularly sheriffs who take the law into their own hands (like this, this, and this).

Sheriff Kirchmeier stepped over the line on the night of Nov. 20 . That was the night that police lobbed tear-gas canisters and flash grenades, shot tennisball-sized rubber bullets, and used water cannons on protesters for five hours as protesters just stood on the Blackwater Bridge in freezing temperatures. Kirchmeier said in a press statement that protesters started fires and threw rocks at police. The more than five hours of live-streaming shows three or four campfires with protesters huddled around. Anyone throwing rocks was acting alone.

On one of the Facebook live-streams, medics said 167 people were treated for injuries or hypothermia. That was later boosted to 200. And yes, social media spokemen played up the injuries because they anger the viewing audience, which at one point was 67,000 people watching one person's feed. That finally brought in the traditional media such as the Washington Post and the Associated Press. The latest development is that Kevin Gilbertt, the man who live-streamed the Nov. 20 events, has had his Facebook page shut down.

Standing Rock is remote and doesn't have great cellphone coverage. But the protesters' stuttering videos used to be worse as the authorities worked to jam their signal. Recently, supporters have helped Standing Rock install their own 4G station so the social media war is joined. Anonymous hackers broke into the Morton County Sheriff's Facebook page and wrote satirical comments, causing the page to be taken down.

The protesters are well aware that the world is watching, and they'll use every angle they can get. The difference between them and the police is they can document their claims. They are now using that evidence to sue Kirchmeier.

But pipeline supporters fight back too. if you watch the live-feeds, you can see the pipeline supporters catcalling in the comments between the hearts and encouragement of supporters. Police shoot down Standing Rock drones. In the opinion pages across the nation, Recently the sheriff's office put out a video with two female deputies saying how hard it is to keep people in line.

It is not truth that is dying so much as objectivity. This reporter went to Standing Rock in mid-November to see the conflict on the ground. What follows describes the documented paper trail and eyewitness observation in a situation that has become muddled by memes and manipulation.