Time running out to keep wasting disease out of Montana

A dire wildlife disease sits on Montana’s doorstep, poised to inundate the state’s prized herds of deer, elk and moose. As more research exposes the disease’s devastating effects, a Montana legislator is sponsoring bills to counter the threat while others renew the call to close Wyoming’s elk feedgrounds.

Within the past month, two research papers added to the evidence showing that chronic wasting disease can significantly reduce whitetail deer populations through deaths not only from the disease itself but also other factors because diseased deer are weakened. Chronic wasting disease is similar to mad-cow disease and causes the animal’s brain to slowly degenerate into a spongy mass and in the meantime, the animal develops abnormal behavior causing it to starve, lose bodily functions and die.

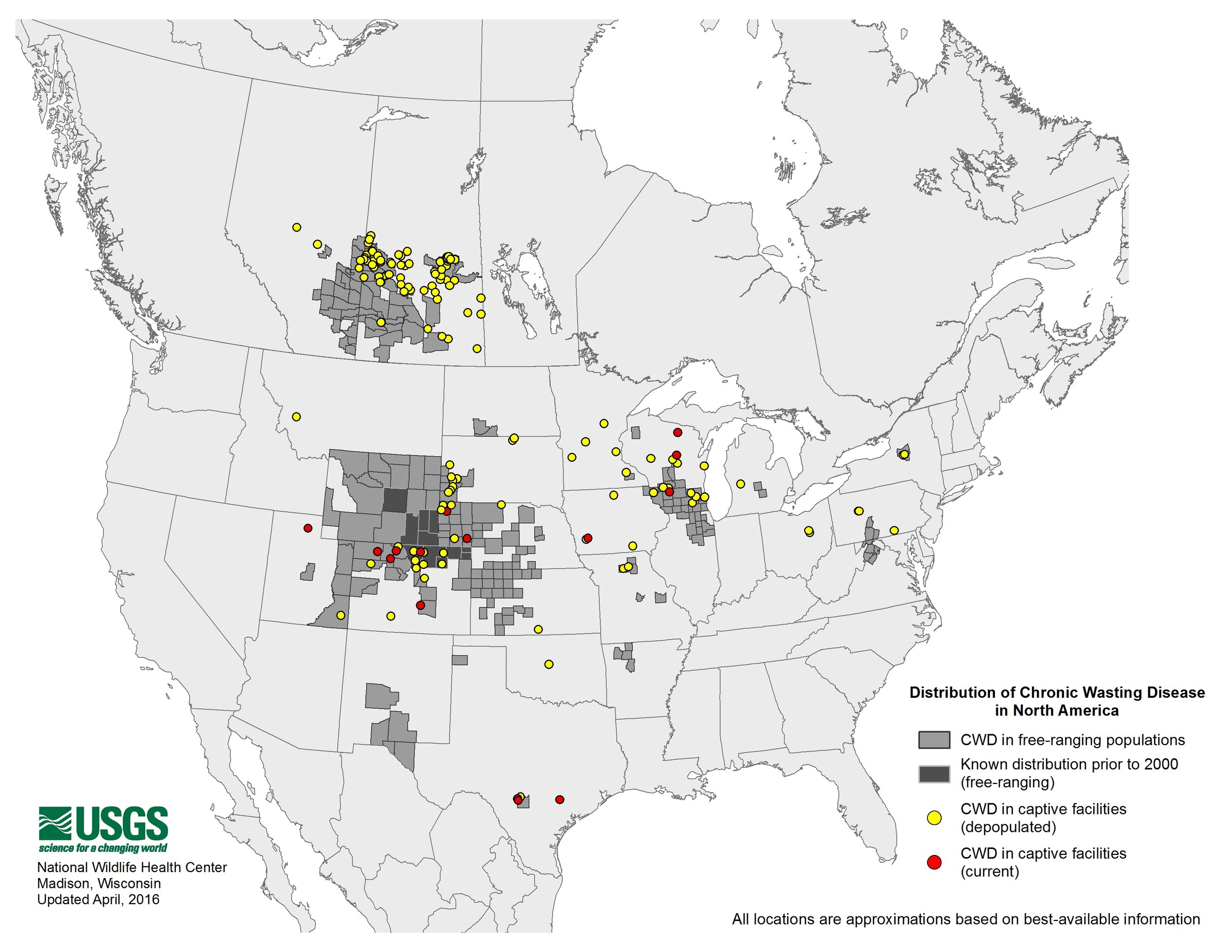

CWD was first identified in captive mule deer in a Colorado research facility in 1967. Since then it has spread to 23 states and parts of Canada. Montana is unaffected so far but is sandwiched between infected populations in Canada and Wyoming.

The disease is spread through prions, a single protein that can end up on the grass and other forage that ungulates eat. The proteins bind to the plants and the soil and cannot be destroyed. The Colorado Division of Wildlife was unable to eliminate CWD from their research facility even after treating the soil with chlorine, removing the treated soil, and applying an additional chlorine treatment before letting the facility remain vacant for more than a year.

So once it becomes established, just like other invasive species, it becomes impossible to eradicate. Animals that eat infested plants get the disease and then spread it to other plants and soils through contact or their urine or feces. Since CWD has been in southern Wyoming and northern Colorado for about four decades, the prions have spread throughout regions frequented by deer and elk.

Sen. Mike Phillips, D-Bozeman, doesn’t want prions spreading into Montana and causing deer and elk herds to die off. Montana’s mule deer herds are just beginning to rebound after a 2013 outbreak of blue tongue, and many of our moose herds are struggling for unknown reasons.

So Phillips has requested bill drafts for a joint resolution urging Wyoming to discontinue its elk feedlots, and a study resolution to take stock of the potential for CWD to negatively affect Montana’s ungulate populations.

Evidence is mounting that CWD would take its toll in Montana.

A Colorado State University study published at the end of August tracked 175 Wyoming whitetails in the Laramie Mountains over seven years and found that one third were eventually infected with CDW, although does had a higher rate of infection, around 42 percent compared to 29 percent of bucks.

Of the 118 deer that died during the study, almost half were infected. Hunters killed 46 deer and 19 of those were infected, which the authors said is higher than expected based upon the infection rate in the overall population.

“The behavioral shifts, including movement patterns, changes in breeding behavior during harvest, decreased reaction time to stimuli, and changes in habitat type used by CWD-positive mule deer may have caused biased harvest proportions,” said lead author David Edmunds.

Nor surprisingly, the scientists found that deer with chronic wasting disease were more than 4 times more likely to die than healthy deer, based upon modeling that factored in a number of possible influences – sex, age, movement and disease. Combined with hunting losses, they predicted the population would be wiped out within 50 years. That stunned the researchers considering that whitetail deer reproduce more easily than mule deer, elk or moose.

“These results support concerns of wildlife managers, wildlife disease experts, and conservationists that this endemic (chronic) disease can negatively impact deer population sustainability at high disease prevalence,” Edmunds said.

This week, another scientific paper published by the U.S. Geological Survey looked at CWD in whitetails in Wisconsin and Illinois, where the disease appeared more recently. Contrary to the Wyoming study, they found that bucks have 3 times more risk of infection and more bucks died of the disease. Other studies have found similar results. The authors suggested “transmission of CWD among male deer during the non-breeding season may be a potential mechanism for producing higher rates of infection in males.”

Edmunds said he may have found more infected females in Wyoming because the resident herds congregate more in particular areas that have, over time, built up high loads of the disease. So CWD might be too new to Wisconsin to have developed the pattern.

“In other words, perhaps our study population is an indicator of things to come, where initially bucks experience higher incidence until a threshold is met when (females) experience higher CWD incidence,” Edmunds said. “For wide-ranging and dispersed populations, bucks may always experience higher incidence than females.”

Animals in dispersed populations have a reduced chance of coming in contact with diseased areas. But in feedgrounds such as those near Jackson Hole, Wyo., animals become concentrated. If even one sick elk arrives, thousands of animals could become infected within weeks. That's why the feedgrounds pose the biggest risk to Montana. Since many of those elk migrate north toMontana, CWD could become established in the state within a year.

Wyoming has been reluctant to shut the feedgrounds down. Elk might go elsewhere and cause property damage. But aiding the spread of CWD could cause more damage.

That’s the warning the Greater Yellowstone Coalition and the Jackson Hole Conservation Alliance tried to convey in their comments to the Wyoming Game and Fish Department in January when the agency was rewriting its CWD Management Plan.

In spite of mounting evidence, Wyoming Game and Fish calls models showing rapid disease spread on the feedgrounds a “worst-case scenario.” The Alliance urged the agency to be proactive.

“A prudent solution would be to begin reducing reliance on supplemental feed through a rigorous program before it becomes a management crisis,” the Alliance wrote. “We request that Wyoming solicit and incorporate comments from Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks… in considering these interstate transmissions and what could likely be a route for CWD entering those states via Wyoming transmission routes.”

The final CWD Management plan published in April states Wyoming will prioritize identification and removal of diseased animals from feedgrounds and will work with agencies to manage wintering populations and reduce their reliance on supplemental feed. But it will consider closing only those feedgrounds where dispersing elk will not cause property damage and makes no mention of coordinating with FWP.