In Wilks negotiations, BLM balanced access, public interest

Last week, to the relief of many Montana hunters and pilots, the Central Montana Bureau of Land Management rejected for a second time any land trade proposed by billionaire landowners Farris and Dan Wilks.

Mark Albers, manager of the BLM’s Hi-Line and Lewistown districts, told the Central Montana Resource Advisory Council on Jan. 26 that the BLM didn’t have the resources to properly review and manage such a trade. Land exchanges require a lot of time and resources, and the Wilks’ plan was particularly complex because it involved parcels in different counties, Albers said.

Albers isn’t exaggerating. The BLM’s Lewistown District Office, real-estate specialists and state directors have already spent two years trying to work with the Wilks to no avail. Since then, Lewistown Office manager Stan Benes has left, and his position has yet to be filled. Albers is having to oversee both offices and BLM's budgets continue to dwindle, thanks to the U.S. Congress.

Not that the BLM isn’t still interested in trying to work out an agreement regarding the Bullwacker Road.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, Montanans used the Bullwacker Road to reach the Bullwacker region of the Missouri River Breaks. According to BLM documents, the BLM formalized that public use in the 1960s through 2000 via a cooperative agreement with the Anchor Ranch.

As recreational use of the road grew in the 1990s, the owners of the Anchor Ranch decided to stem the traffic in 2000 by declaring the road private. They were forced to reopen the road briefly in 2009 after the Blaine County attorney decided decades of public use qualified as a prescriptive easement. But in 2011, a state district court judge disagreed, declaring the road private.

Since then, the BLM has tried to restore access to the Bullwacker area and had new landowners to deal with when the Wilkses bought the Anchor Ranch in 2012. Soon after, Wilks representative Jimmy Williams, a real estate broker out of Cisco, Texas, reached out to the BLM to see if there was a way to trade Bullwacker access for federal land inholdings, including the Durfee Hills on the NBar Ranch farther south in Fergus County.

The history that follows shows the extent to which the BLM worked with the Wilkses while trying to protect the public interest. It is based upon electronic and written communications, copies of which were gained through a Freedom of Information Act request submitted by WildEarth Guardians attorney John Meyer.

--

In January 2013, then-BLM Central District Manager Stan Benes told Williams that the BLM might consider a land exchange because BLM State Director Jamie Connell was “committed to regaining public access in the Bullwacker area.”

It appears Benes made suggestions for which lands the Wilkses might offer, including those that fronted and provided access to the Little Snowy Mountains. Some of those parcels had been part of the Janet Lewis Ranch before the Wilkses bought it along with the adjacent NBar Ranch and the Anchor Ranch farther north near the Bullwacker area.

However, in preparation for a meeting on March 1, Williams denied that the Wilkses owned the Janet Lewis property – it’s possible they hadn’t closed on it yet - and stated that the Wilkses under no circumstances would provide “extra access to the Little Snowy Mountains.”

“This position by the Wilks is not negotiable,” Williams said in a Feb. 20 email.

The public didn’t yet know of a land trade in the works, but Benes knew how hunters would probably respond to the Wilks’ request for ownership of the Durfee Hills. So he knew any land offered in exchange had to be good.

“I do believe that a loss – as it would be perceived by area hunters and pilots – of the Durfee Hills, without an equal measure of access in that same Snowy area in return, would result in a similar non-negotiable situation, “Benes wrote on Feb. 25. “Perhaps there are options that would not include the Durfee Hills.”

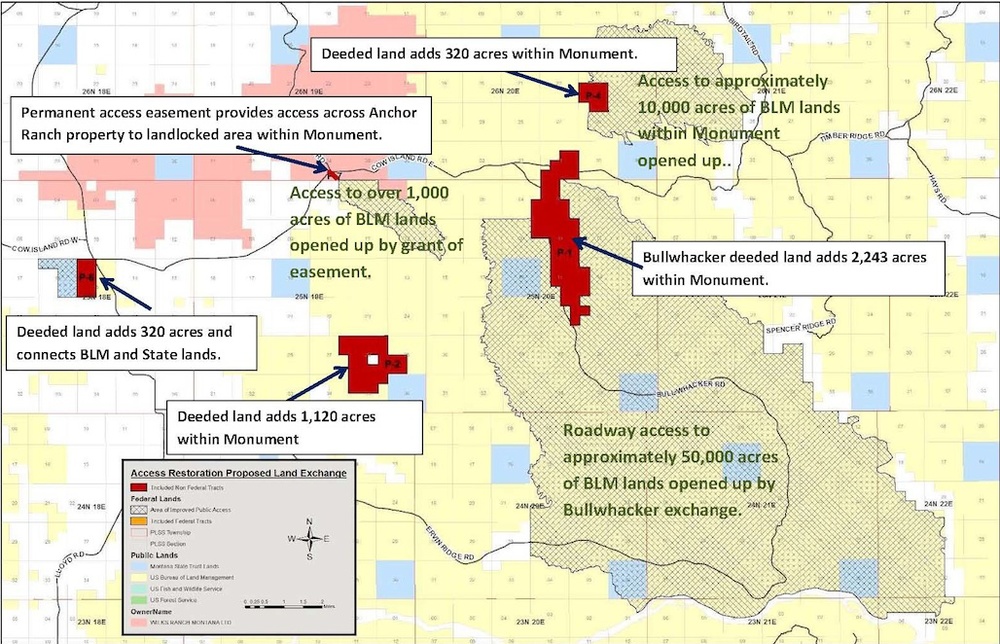

As the bartering discussions began at the end of March, Benes handed Williams over to Jim Ledger, BLM Realty Specialist and Access Coordinator. Williams and Ledger worked on identifying the federal and private parcels in the Wilks’ proposal and developed reference maps with the parcels in question marked “F” for federal and “P” for private. All 26 “F” parcels were on the NBar Ranch in Fergus County and the 6 “P” parcels were on the Anchor Ranch in Blaine County. The deal included an easement for the public to use the Bullwacker Road.

By the end of April, Williams was gaining confidence in the trade and asked Ledger if the trade and its specified parcels would be announced at the May 8 Resource Advisory Council meeting.

Private citizens representing various public-land users sit on the RAC, which meets quarterly to advise the BLM district on decisions and policies.

Ledger, who was still calculating acreages and reviewing the characteristics of each parcel, didn’t share Williams’ confidence.

“We do not look at it that we have a final agreement on the parcels with you yet – and we’re not going to discuss that level of detail with the public until we do,” Ledger wrote on May 3.

A few days before the RAC meeting, Ledger explained to Williams the BLM’s problems with the Wilks’ proposal.

Both the BLM and the Forest Service devise resource management plans to guide district level decisions every 15 years or so. The Judith-Valley-Phillips Resource Management Plan didn’t allow Ledger to trade of some of the BLM parcels because they had either legal public access or paleontological value.

Six parcels had road access. The Durfee Hills parcel, F-15, does not, but landing strips allow the public to fly in, so it technically has access.

Access to public land in Fergus County is woefully poor, so Ledger said he couldn’t justify amending the land-use plan to give up accessible parcels unless he got equally accessible parcels in return. He renewed Benes' request for the Little Snowy Mountains.

“The question then becomes, ‘Are the Wilks willing to consider an exchange that will mitigate for the loss of public access in Fergus County?’” Ledger said. “ The Wilks’ acquisition of the Janet Lewis property would seem to present opportunities for improved access to existing public lands in the Little Snowy Mountains.”

Williams dug in, refusing to trade any land that would add more access to the Little Snowy Mountains. Knowing the BLM managers valued Bullwacker access, Williams tried to play a little hard ball, suggesting that the Blaine County part of the proposal could be dropped so the parties could focus on trades on the NBar Ranch.

“By keeping all the lands in the same county, it will then truly appeal to the Fergus County residents,” Williams wrote on May 11.

Ledger seemed to get the message. Maybe worried about losing the Bullwacker option, he suggested a face-to-face meeting.

After discussions with Benes, Connell, and Assistant State Director Kristen Kitchell, Ledger went back to work with Williams, modifying the Wilks proposal by the end of August. The new proposal would trade around 8,300 acres of Wilks’ land plus the road easement for around 8,800 acres of federal land, including 2,785 acres in the Durfee Hills.

Although a few parcels differed from the original proposal, 22 of the proposed 27 federal parcels were still supposed to remain in public ownership according to the resource management plan.

All the private land to be traded was still in Blaine County, a fact Ledger noted in his report to BLM managers. The one selling point remained that one private parcel, P-1, provided access to more than 69,000 acres of public land, both federal and state, in the Bullwacker.

“With limited exception, the Wilks have been unwilling to modify their original exchange proposal,” Ledger wrote. “Opposition to the exchange is expected to come primarily from Fergus County, from both the public and county commissioners.”

The negotiations continued until mid-September, when the road easement was dropped in favor of adding two private parcels that contained Bullwacker Road. That created a land trade of about 17,600 private acres for about 9,600 federal acres and would give the Wilkses an easement to their property.

At that point, the Wilkses planned to meet with BLM managers to finalize the proposal when they were put on hold by the government shutdown. The federal budget wasn’t approved by Oct. 1, 2013, because some members of Congress wanted to defund the Affordable Healthcare Act. As Congress haggled for the next 17 days, BLM employees couldn’t work.

Eventually, the meeting took place, and BLM managers were apparently able to convince the Wilkses that if they wanted a trade, they needed to be wiling to give in on the Little Snowy Mountains.

So in early December, Williams put forward the third proposal, which included some of the former Janet Lewis Ranch along almost 4 miles of Red Hill Road along the northeastern edge of the Little Snowy Mountains. But the two parcels containing the Bullwacker Road that had been added in September were gone.

Still, the Wilkses were offering more than 13,200 acres for almost 7,900 of federal land, which Williams said “qualifies this as overwhelmingly benefitting the public.” The federal land was broken into 27 parcels while the private land was in seven parcels, with one enlarged to include part of the Bullwacker Road.

The BLM managers agreed the trade was more positive and started getting input from other groups and agencies, including Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. But initial feedback was skeptical at best.

--

At the end of January 2014, Ledger told Williams that the next decision would probably determine whether the trade moved forward. So the BLM was reaching out to more groups, including the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation and the Friends of the Missouri River Breaks Monument, “to be sure that we haven’t limited input from only negative sources.”

Dealing with 27 federal parcels, most of which had public access, was problematic, so Ledger suggested that Williams simplify the proposal to 10 parcels starting with F-15, the Durfee Hills, and F-14 nearby.

In trying to scale down the proposal, Ledger may have been mindful that more a decade earlier, an independent audit found that the BLM had operated under a "politicized" climate in which appraisers are under "undue pressure" to bend rules and face "personal jeopardy" from BLM and Department of Interior managers eager to close deals. Many trades provided government land to private individuals at below market values, or set inflated values on private parcels to force the government to offer more land in exchange.

The problem for the Montana BLM was that, with the traded acreage reduced, Williams again decided to play hardball and removed most of the Little Snowy Mountain parcels. Benes wasn’t cowed, armed with the knowledge that some organizations were encouraging him to “proceed with our Plan B, which is one of several options to build a road around the private Bullwacker parcel.” He asked Williams to add the parcels back in and suggested to Ledger that he add a few more federal parcels in exchange.

A week later, Benes told Williams that since word was getting out, it was time to go public with the proposal. He cautioned that interest was growing in building a new Bullwacker Road and that the RMEF had voiced interest in working with the Wilkses on restoring access.

“We should have a pretty good read on where the public opinion lands on the potential land exchange by the end of next week. That will be of great interest to the State Director on how to proceed,” Benes wrote Williams.

As Benes and Ledger predicted, the Wilks’ proposal was controversial. A petition opposing the exchange was already circulating. Those hunters who didn’t fly into the Durfee Hills wanted Bullwacker Road access back, but others didn’t want to surrender the healthy elk herd that inhabits the Durfees. The Friends of the Missouri Breaks Monument, being unconcerned with Fergus County, wanted the Bullwacker access. Many didn’t want to give up the Durfee Hills because they didn’t like giving up public land to rich landowners that had already bought up much of the property in the area.

As the opposition became more vocal, a frustrated Williams tried to amplify the voices of those who supported the trade.

“You should see more vocal public support for the exchange soon including positive sides of the story that have not been expressed. I wanted to give you notice as so far we have kept quiet but that is changing,” Williams said in an April 2 email to Benes.

A few weeks later, after the BLM received a petition with 1,600 names opposing the trade, Williams sounded more conciliatory as he asked Benes what the BLM wanted in exchange for the Durfee Hills. Benes again suggested the Janet Lewis property along the Little Snowy Mountains as “something more likely to receive broad public support.”

“The State Director has told me on three occasions now that, considering all the aforementioned responses, no, we will not move forward on the land exchange as proposed,” Benes wrote.

A few weeks later, after the Wilkses told the press that they felt blind-sided by the BLM, Benes emphasized to Williams that the possibility of an exchange was still alive.

“We feel, as did RMEF when I joined them for breakfast last Thursday, that there are adjustment to that specific proposal certainly worth discussing,” Benes wrote on May 3.

BLM State Director Jamie Connell met again with the Wilkses on May 12 and put Ledger back to work with Williams on the fifth proposal. Instead of the parcels along Red Hill Road, Williams offered a Little Snowy Mountain parcel about 3 miles east of Red Hill Road that included a stretch of Snowy Mountain Road.

On June 2, Benes said no. Public opinion might only support a trade that included the original two Red Hill Road properties.

On June 17, Williams tried a final time with a surprising proposal. He offered 4,003 private acres in Blaine County for 2,803 federal acres in Fergus County. But for the first time, the federal parcels didn’t include the Durfee Hills. However, the private parcels didn’t include the Little Snowy Mountains, and the BLM would still be trading away other federal parcels that had public access.

Benes wasn’t optimistic, but he set up another meeting with the state directors. In the meantime, the BLM was moving forward with an environmental study of other ways into the Bullwacker.

On Aug. 11, when Williams learned that the BLM had finally decided against any exchange, he wrote directly to the State Director, asking her to consider the June 17 proposal, which he said the Wilkses would leave on the table indefinitely.

“It is unfortunate that the BLM has chosen not to allow the public to view this modified exchange,” Williams wrote.

Benes responded a final time, saying none of the proposals Williams brought forward passed public muster for one reason or another.

“I can understand your frustrations in dealing with what must have seemed like a constantly moving target,” Benes wrote.

--

Fast-forward almost year to July 2015 when Benes saw the land-trade specter raise its head again.

Jimmy Williams was gone, but in his place came Darryl James, a Kentucky-born public-relations consultant who specializes in federal and state regulatory processes such as the National Environmental Policy Act.

The Wilkses must have taken Benes’ words about the need for public support to heart, and James took control of communication with the public from the start.

Before James sent yet another Wilks proposal to the BLM, he had already invited FWP and 13 hunting and land advocacy groups to two private scoping meetings; one to discuss options and a second a month later to reveal the land-trade proposal.

The hunters and Fergus County residents who had been the most vocal opponents a year before were not included in the round-table presentations. Private-property and agriculture groups were.

James also sent the proposal out to the public, not waiting for the BLM to do its own public relations.

James’ July 9 proposal was similar to many brought forward by Williams: In addition to four private parcels and the Bullwacker easement in Blaine County, James added what Benes desired: the Janet Lewis estate parcels and an easement along Red Hill Road. For that, the Wilkses wanted 12 federal parcels in Fergus County including the Durfee Hills. The trade would involve about 5,000 acres on each side.

To appeal to hunters, the Wilkses added one more thing: the promise of public hunting on their Fergus County ranch. While that wouldn’t play into the BLM’s decision-making, it could engender more public support than previous proposals.

With the public already aware of the proposal, Benes gave the RAC copies of James’ draft proposal on July 16 and asked the council members if it should be incorporated in the environmental study of a new Bullwacker Road.

The RAC didn’t endorse the proposal partly because of questions as to whether the Wilks trespassed on BLM land when they constructed roads and fences in the Durfee Hills starting in late September 2014.

On Aug. 14, 2015, BLM surveyors submitted their findings as to the location of the roads and fences, and the Wilks brothers had 30 days to object. Four months have passed, and the BLM has yet to announce whether or not the Wilkses trespassed.

On Aug. 24, James sent out the finalized proposal, which contained only slight changes, mainly that they would consider hunters’ and pilots’ requests for additional access.

James arranged for the RAC to be able to access the Bullwacker Road during their October meeting, and the Wilkses opened the road up to the public last fall, although it’s unlikely they’ll keep it open.

With the BLM on the verge of giving up on the idea of building a new road into the Bullwacker area, hunters again debated whether road access through the Anchor Ranch was worth losing the Durfee Hills. Many, including the Montana Wildlife Federation and the Montana Bowhunters Association, concluded it was not, especially after the Wilkses refused to give hunters a guarantee that they would be allowed to hunt on the NBar Ranch.

Those groups breathed a sigh of relief last week.

--

If the past three years is any indication, the issue isn’t dead. With the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge standoff in Oregon adding fuel to the public-lands conflict and some Republican presidential candidates saying they support selling public lands or giving them to the states, the Wilkses may have additional pull in the future.

On July 27, CNN reported that the WIlks Brothers had donated almost half of the $38 million sitting in the coffers of Texas Sen. Ted Cruz’s SuperPAC. Cruz is one of seven GOP candidates that strongly support the privatization of U.S. energy reserves and land.

While hunters assume that the Wilkses want the land to have their own private hunting preserve, it could go farther than that.

The NBar Ranch and the Durfee Hills sit atop the Heath Shale, what some geologists assume to be one of the next best natural gas reserve behind the Bakken Shale.

A number of wells were drilled in what is called the Wildcat Fergus field in the 1950s by hopeful gas companies. They were unsuccessful, but that was before modern fracking technology, which is where the Wilks made their fortune.

The federal government owns many of the mineral rights below both the federal land and the Wilks land. If a land trade had gone through, the Wilkses may have acquired those rights and not had to pay the government for the leases, should they want to develop natural gas wells.