Alternatives proposed in BLM mining ban to benefit sage grouse

The U.S. Bureau of Land Management is moving ahead with a proposal to stop future mining development on more than 10 million acres of federal sage grouse habitat.

On Friday, the BLM released its draft environmental impact statement of the ramifications of freezing all future mining claims on federal land in six states, including Montana. That starts the clock on a comment period that will close on March 30. It’s the second chance for the public to comment, the first being the scoping period that occurred in late 2015.

“We appreciate the input we’ve received from states, tribes, and other important stakeholders to help develop this draft analysis of the proposed mineral withdrawal,” said Kristin Bail, BLM assistant director for resources and planning.

The EIS analyzes four options that would set aside differing total acreages, in addition to a “No action” alternative, which would allow an estimated 114 exploration projects within core sage grouse habitat over the next 20 years.

The BLM could not stop mining development without the proposed ban due to the 1872 Mining Law, which allows any mining on federal land as long as it meets federal standards, even if its existence would bring the sage grouse closer to extinction.

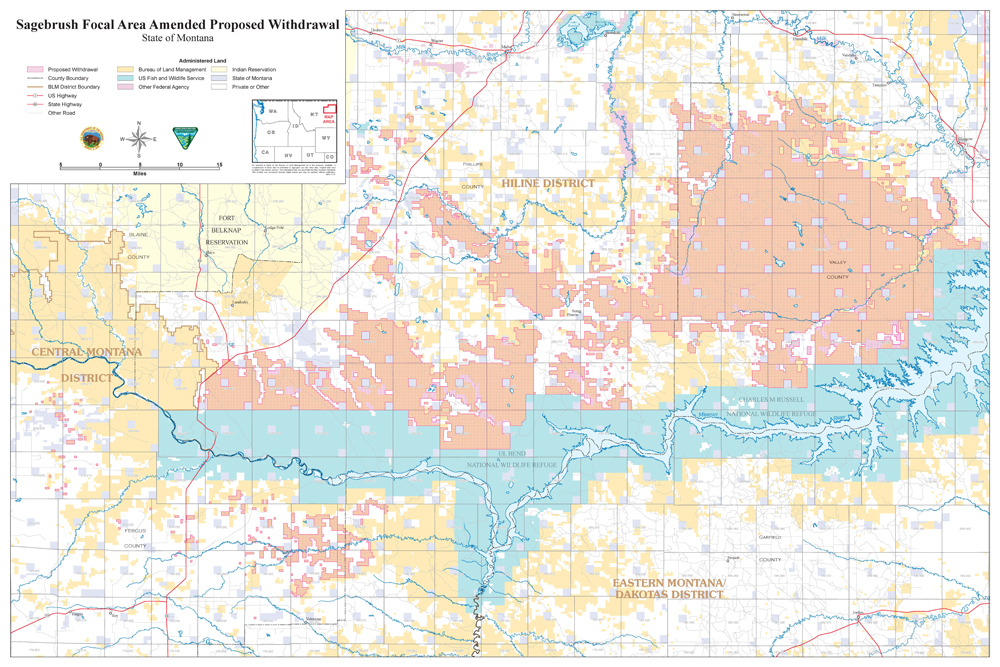

The BLM’s preferred alternative would remove 9.95 million acres from being subject to future mining claims. Most of Montana’s sage grouse habitat sits on private land so the mining ban would affect only 877,000 acres of BLM land north of the Missouri River, mainly in Fergus, Valley and Phillips counties.

Only about 1 million acres total in all six states have a moderate to high probability of sitting on top of extractable mineral deposits. If that were taken off the table, the preferred alternative would still allow 38 mining exploration projects.

Each of the other three alternatives would set aside at least 9.39 million acres but would open up more ore-rich areas to mining claims, resulting in more exploration and mining projects.

Montana Attorney General Tim Fox argued that the ban wasn’t necessary in Montana because only 12,500 acres have a high potential of containing ore so no one would bother exploring the rest. Alternatively, Fox said the BLM did have the power to limit any mine on the high-potential land so a ban wasn’t needed.

“Federal action that is so obviously intended merely to cater to political special interests without providing any substantive protections violates our State’s sovereignty and upsets the principles of Federalism so firmly planted in our Constitution,” Fox wrote in his January 2016 comments.

States like Nevada and Idaho, which either have an established mining economy or want to encourage one, are also pushing to keep more land open to mining. Idaho Gov. C.L. “Butch” Otter and some Nevada county commissioners called the ban on new mining claims an “over-reach.” The Idaho Mining Association agreed.

“We agree with Governor Otter that the process behind proposed amendments to federal land-use plans imposed unprecedented and unnecessary restrictions on Idaho farmers, ranchers, sportsmen, recreationists, employers and specifically on Idaho’ mining industry,” Jack Lyman, IMA executive vice president, wrote a year ago. “The Department of the Interior proposal to withdraw over 10 million acres of federal lands from mineral entry and new mining operations – 3.8 million acres in Idaho – is unprecedented and constitutes the largest withdrawal in the history of Federal Land Policy and Management Act.”

So Nevada proposed keeping 486,000 federal acres open to mining in the northern part of the state in exchange for about 390,000 acres elsewhere in the state. The problem is that those 390,000 acres are not within designated core sage grouse areas called Sagebrush Focal Areas or SFAs – they cover regions nearby that don’t have habitat that is as good.

Similarly, Otter proposed an alternative allowing mining in all federal lands in Idaho that have “high” probabilities of mineral deposits. That equates to about 538,000 acres out of Idaho’s 3.8 million acres that would remain open to mining.

The last alternative would allow mining in areas identified has having a high mineral potential – almost 559,000 acres - in all six states.

That may not seem like much out of almost 10 million acres, but at this point, sage grouse may not be able to withstand the loss of another half million acres of habitat. Populations have crashed from what they were in the 1960s and ‘70s.

In 2010, the Service determined that the greater sage-grouse warranted Endangered Species Act protection because of population declines caused by loss and fragmentation of its sagebrush habitat, coupled with a lack of regulatory mechanisms to control habitat loss.

With their soft “bloop-bloop” mating calls, sage grouse can’t attract mates with noisy industry nearby. Males strut for hours but no females ever visit. As a result, few mating grounds or leks survive near mining or oil and gas sites.

Females need tall healthy sagebrush within a short distance of a lek to rear their chicks, since sagebrush provides cover from predators and food in the form of leaves and insects. But surface disturbance from large-scale mining is significant, often affecting thousands of acres, completely altering the existing habitat to accommodate industrial activities.

As the sagebrush sea has been torn up for development, farming or resource extraction, or burned in extensive prairie wildfires, populations have dwindled. From hundreds of millions in the 1960, the FWS estimates only 200,000 to 500,000 remain across 11 states.

The states and federal agencies were able to avoid a listing of the sage grouse because state conservation plans were created and agencies rewrote land-use plans to conserve sagebrush habitat. Seeing that all these efforts were in place, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Director Dan Ashe decided against a listing in September 2015 but warned that the agency would not hesitate to list if the plans were not followed.

Those plans included banning future mining in core sage grouse habitat. As Earthworks Northwest Director Bonnie Gestring pointed out, the FWS concluded that all mining needed to stop in core areas because of the various threats to healthy habitat.

“The proposed withdrawal falls short of the (National Technical Team) recommendation to protect priority habitat, and does not include the validity exams or buyouts for valid existing rights,” Gestring wrote in her January 2016 scoping comments. “Despite efforts to regulate the Zortman Landusky Mine, significant adverse effects to vegetation, wildlife habitat, soils, water quality and water quantity occurred. If these impacts were to occur within the Greater Sage Grouse priority habitat areas, adverse impacts to sage grouse and sage grouse habitat would result.”

However, the EIS allows existing mining and valid mining claims to continue, so it’s not a complete ban. But the agencies are trying to keep the remaining pristine habitat from being degraded. That helps not only sage grouse but up to 350 other species that live in sagebrush ecosystems.

If any EIS alternative is approved, it will remain in place for up to 20 years, and can be renewed in 20-year increments.